Regional film industries in the northeast are making waves across the world

April 19, 2024

In the past few years, Indian cinema has taken strides both in terms of commercial and critical acclaim. The birth of the ‘pan-Indian’ movie, featuring larger-than-life characters who appeal to audiences across the board, has swept the country. Added to that is the wealth of regional and independent films that are discovering audiences thanks to wide releases as well as online streaming platforms.

But at the same time, other nascent film industries have felt the pinch and are still committed to their struggle of telling great stories and promoting their heritage in a unique form. Two emerging film industries from two states in the northeast show the nature of their issues and the brilliance of their craft, which the rest of the world seems to be missing out on.

In the shadows

In northeast India, one vernacular film industry dominates over others in terms of sheer numbers: the Assamese film industry. Previously called Jollywood, it is among the oldest film industries in the country. Starting in 1935 with its first film Joymati, the Assamese film industry constantly grew in the early twentieth century.

The enshrining of Assamese as one of India’s official languages in the Constitution gave it governmental protection and funding, which allowed Assamese arts and films to continue being produced, reaching a new stage of increased production in the late 60s. This was in part because of stalwarts like Phani Sharma, Anil Choudhury, and the legendary Bhupen Hazarika.

Within these regions, where one language dominates a particular aspect of life, it tends to do so to the detriment of other dialects and languages around it. This has been the case with Bollywood, which has resulted in much smaller industries in local dialects and languages throughout the Hindi heartland. In most cases, the Hindi film industry seems to have subsumed movies with these dialects and languages.

However, that has not been the case with Jollywood. Thanks to the linguistic diversity of the northeast and the small space that these languages share, regional film industries such as those based in Manipur, Meghalaya, and Tripura blossomed in the 70s and 80s. Aided by technicians and artists who had plied their trade in Assamese cinema, these nascent film industries told pathbreaking stories from the beginning.

Speaking on the openness between the various film industries, National Award-winning film critic Utpal Borpujari explains, “There has never been any step-motherly treatment from Assamese cinema towards other smaller, regional film industries. Actors and crew have worked across state and linguistic lines. If anything, the spirit of collaboration has increased in recent years as the youth are a lot more open-minded.”

The jewel blooms

Starting in 1972, Matamgi Manipur was where Manipur cinema started. A Meitei language film, it was directed by Debkumar Bose and dealt with the diverging views of two generations. So from the first instance itself, one could see the cross-collaboration in various departments. Bose himself was Bengali and often directed Assamese films. The first Manipuri film by a Manipuri director was Sapam Nadia Chand’s Brojendragee Luhongba in 1973, in which he also starred and did the music.

In the five decades following the arrival of Manipuri cinema, it has gone from strength to strength. While the volume of releases has decreased slightly in the past few years, it remains — after Assamese cinema — the most prolific film industry in the northeast. During this time, Manipuri films have regularly won big at the National Film Awards, often outside their linguistic categories. Films from the industry have also found favour with international audiences, with Aribam Syam Sharma’s Ishanou (1991) being screened at Cannes’ Un Certain Regard section, and was recognised as a ‘World Classic’ at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival, the only Indian film to be recognised so.

Manipuri cinema has retained its penchant for meaningful stories, with films like Oneness by Priyakanta Laishram in 2023, which was hailed as Manipur’s first gay-themed film, and Romi Meitei’s Eikhoigi Yum in 2021, which won at the 69th National Film Awards and was an official selection for Jio MAMI 2022.

Borpujari elucidates on the nature of Manipuri films, “Thematically, Manipuri films are unique, and are often labours of love and passion projects. Although the commercial movies they make are heavily influenced by Bollywood.” The presence of out-and-out commercial films like Inspector Yohenba 1 and 2 (inspired by the Salman Khan-starrer Dabangg series) show that Manipuri cinema has the scope to experiment and successfully deliver different kinds of films.

Cloudy with a chance of films

In Meghalaya, things are slightly different. While the majority of Manipuri cinema makes films in the Meitei language, there’s no overarching language as such within Meghalaya, with Garo and Khasi being the two most spoken languages after Assamese in the state. The growth of Garo and Khasi films has been rather slow and laborious since the first Khasi film in 1981, Ka Synjuk Ri Ki Laiphew Syiem (The Alliance of 30 Kings). It has been only in the last fifteen years that Garo and Khasi cinema have picked up some momentum, which is down to two visionary auteurs, Pradip Kurbah for Khasi cinema, and Dominic Sangma for Garo cinema.

Kurbah, who learned the ropes in Bollywood, spent over ten years trying to get his 2014 National Award-winning science fiction film Ri: The Homeland of Uncertainty off the floor. Upon being asked about using a science fiction setting to explore state terrorism, Pradip Kurbah explained, “In Meghalaya, each filmmaker has their own style when it comes to making films. Due to the diversity of cultures as well as miscegenation, every filmmaker is unique in the way they approach the craft.”

Kurbah’s latest film, Iewduh (2019), was screened at the 2019 Busan Film Festival and received rave reviews on its portrayal of the linguistic and cultural diversity of Meghalaya and the issues associated with it.

Sangma has been single handedly responsible for bringing Garo cinema to the world. His first feature film, Ma.Ama (2018), won the Best Cinematography Award at the 22nd Shanghai Film Festival and his newest film, Rimdogittanga (Rapture), was screened at the 2023 Locarno Film Festival. An alumnus of the Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute (SRFTI), Sangma takes a keen interest in every aspect of filmmaking, and often seeks to cast non-actors and locals in small roles.

Commenting on the community aspect of storytelling as well as the paucity of Garo films, he said, “When I set about to make Ma.Ama, I hit upon the realisation that there were no reference points when it came to Garo cinema. Sure, there were a couple of films that had been made in the 80s, but nothing major to serve as a waypoint for future storytellers and filmmakers. So whether I like it or not, I am the reference point and the pioneer here, which is why I have to look at the entirety of my filmmaking process a lot more seriously. Filmmaking in Garo Hills has to be a community effort. While funding can come from various sources, the heart of my films is rooted in the community and the cultural identity of Garo Hills.”

A Need for screens

While the northeast, not just Manipur and Meghalaya, has a treasure trove of stories and storytellers just waiting to spin their yarns, there is a chronic lack of funding when it comes to films. While early in the last decade, the OTT boom sought to source all kinds of films and became a haven for independent as well as regional filmmakers, this has changed since the pandemic.

“While earlier there was talk of having most digitally made films on OTT, regional films quickly fell out of favour. Now it has reached a point where it is difficult for even an Assamese film to secure a preferential OTT release, so what hope is there for the smaller ones? Directors need to be able to recoup their production costs at the very least, and OTT platforms are not able to offer that kind of money,” says Borpujari.

Kurbah recognises a bigger issue at hand, “The primary obstacle facing contemporary Khasi cinema, and regional cinema by extension, is the lack of cinema halls. There are only two cinema halls for Khasi films in all of Meghalaya. So while locals generally like Khasi movies irrespective of their demographic, encouraging them to come to theatres instead of sticking to OTTs and producing high quality films is crucial. The government’s initiative to establish 30 more cinema halls in the state looks to be a step in the right direction.”

These, alongside efforts from established directors as well as film critics, might just herald a new age for cinema in the northeast. As such, Kurbah and Sangma have co-founded the Kelvin CInema Festival. Recognising the latent talent in the storytelling ability of the northeast and the scarcity of film festivals and infrastructure there, the festival aims to nurture this spark. “Before joining SRFTI, I hadn’t watched any world cinema; I didn’t even know that such a cinema existed. I only watched Hindi films and Hollywood films. SRFTI opened the door to a different world… I was wasting my time on films that could have dulled my perception of life. I don’t want that to happen to young aspiring filmmakers from the region. With the Kelvin Cinema Festival, both Pradip Kurbah and I aim to bring good films from across India, introduce filmmakers from different regions and create a space to learn various aspects of filmmaking, festival strategy, distribution, etc.” Sangma explains.

So while Manipuri and Meghalayan films are earning plaudits the world over, we need to recognise and protect this unique art as well. And that starts with exploring and encouraging a different way of looking at cinema, as well as fostering a cinematic ethos that celebrates plurality and cross-cultural collaboration.

Monkey Buffet Festival

On the last Sunday of November, a lavish banquet is laid down among the ruins of the Phra Prang Sam Yot temple in Lopburi, Thailand. Fresh fruits and vegetables are served to honour the guests in hopes of receiving their blessings. What makes this celebration unique is that the guests are not humans but monkeys -- macaques, to be precise.

How did this tradition come to be? It is believed that these gregarious Old World monkeys bring good luck to the area and its people. So, the feast started back in 1989, with a local resident who wanted to honour the simian population. Over the years, this simple act has taken the shape of a full-blown carnival with dancers in monkey costumes and more.

Being one of the oldest and most historic cities in Thailand, Lopburi has caught the interest of travellers who flock in large numbers to this city to witness this unique event. Tourism has thus become central to Lopburi, a city which boasts of countless ancient sites dating from varied civilizations and dynasties.

Apart from bringing prosperity and luck to the region, this festival is evidently a one-of-a-kind spectacle to witness.

Rent-a-Man in Japan

How many times have you missed trying out a new restaurant or watching the latest flick at the theatre because you had no one to accompany you? While solo luncheons and dates with yourself are emerging as a popular way of reclaiming ‘me-time’ around the globe, there’s a parallel option available in the cities of Japan that has raised some eyebrows before melting hearts.

This is the service of renting a person – for reasons that vary from simply wanting company for lunch, or saving face at a social event where plus-ones are expected (how we relate to that!), to even needing moral support during difficult times. Like in the case of Akari Shirai, who wanted to visit her favourite restaurant in Tokyo before leaving the city after her divorce.

She opted to hire Shoji Morimoto, a man who is popular for doing nothing. “I felt like I was with someone but at the same time felt like I wasn’t… I felt no awkwardness or pressure to speak. It may have been the first time I’ve eaten in complete silence,” Shirai told the Washington Post, adding that this was just what she needed.

The ‘rental-san’ who accompanied Shirai has inspired TV shows and books and gained a cult following in recent times. And several other rental-sans are enhancing the social dynamics of the country in different ways… which makes us wonder: would this work in any other region on the globe? Hit reply to share your thoughts!

The Shape-Shifters

Feeling hot hot hot...? Summertime can be fun and cheery, but too much heat can be a killjoy – not to mention the impact it has on our one precious planet. As temperatures continue to rise around the globe, experts are trying their best to prevent 500 days of summer (nothing against the film). And, to do that, they have turned to innovations in urban engineering – where the biggest challenge is to make a city liveable and eco-friendly – as the primary strategy.

How are we going about it?

By borrowing from past traditions and innovating with futuristic insights. Architects and researchers are picking traditional architectural elements from around the globe – like the ‘skywells’ in China, badgirs or wind towers in Persia, jaali (a type of perforated block) in India, or mashrabiya or wooden lattice in the Middle East and North Africa – and finding ways to integrate them with modern technology. Although, they are still at a nascent stage.

Meanwhile…

Installing green roofs or painting both the roofs and walls of a house white (think: Rajasthan) has been one of the simpler and more economical strategies. New York City has painted over 6 mln sq ft of rooftops white to reflect the sun rather than absorb it, while Los Angeles has followed suit.

Similarly, a pilot project in Barcelona is developing a network of ‘climate shelters’ by integrating blue-green and grey infrastructures. Paris, on the other hand, has developed an interlinked network of “cool islands” where people can seek refuge – from parks and forests to swimming pools.

What next?

More innovations. These interventions are just the start. As climate continues to change, we can expect more experimentation and boundary-pushing technologies in architecture to help cool our warming cities – maybe even completely revolutionising the image we see when one utters the word urban design.

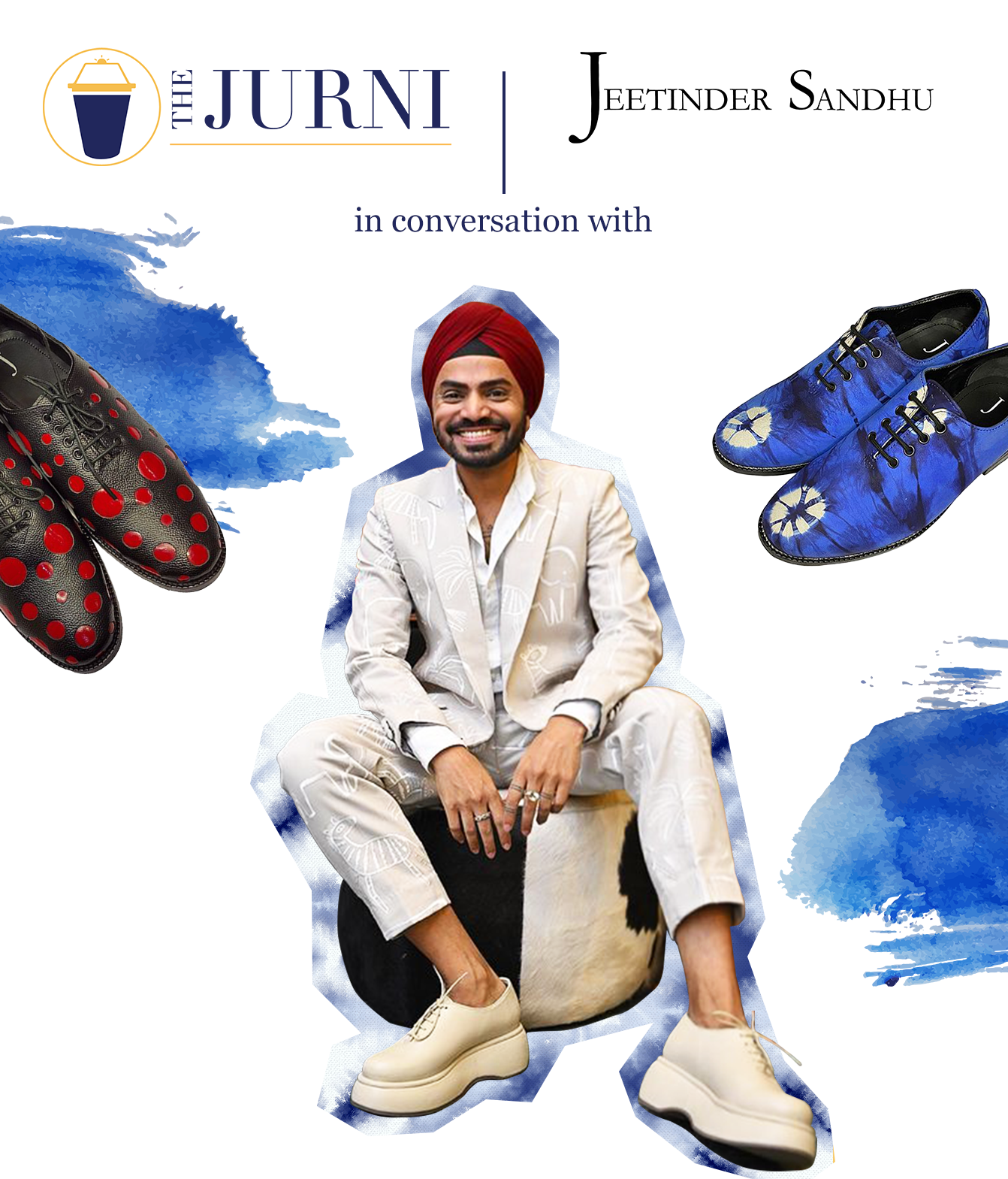

Indian Roots, Global Expressions: Jeetinder Sandhu's Vision for the Future of Fashion

In the world of haute couture, what does the ability to blend diverse cultures into breathtaking creations look like? The answer – Jeetinder Sandhu, the visionary fashion artist whose masterpieces epitomise the fusion of Indian heritage with a global flair.

With a storied background of living in Delhi, London, and Rome, Sandhu’s design sensibilities have been profoundly shaped by the cultural tapestry of each city. His gender-neutral approach to fashion celebrates individuality and self-expression, elevating his creations to a new level of inclusivity.

He sat down for an exclusive chat with The Jurni. Excerpts:

As a travel and culture newsletter, we appreciate how cities enhance our lives. Have you felt moved by any travel or culture experiences that ended up influencing your design sensibilities?

I have always been fond of travelling from a young age and have the ability to really immerse myself in and adapt to new cities and cultures. I have lived in the great city that is Delhi. I have also lived in London for close to seven years. And I lived in Rome as well. Each of these has been a cultural experience that is unique and each has influenced my design thinking in their own ways. They represent very diverse and different ways of life. Both Delhi and Rome have a long civilisational history and one finds the past and the present fuse into so many different aspects of life every day. London on the other hand is a fashion powerhouse and was instrumental in developing and influencing my design thinking when I was in my early days at university. It let me explore myself and identify my style, as well as how I wanted to express myself. Each city that I have lived in has been such an important part of my journey – in not just defining who I am today as a person, but also as a designer.

From brogues to loafers and embroidery to upcycled wall hangings – there is nothing we haven’t seen in your designs. Where do you draw your inspiration from?

I draw my inspiration from my Indian roots. The privilege of living in different parts of India and the opportunity to travel widely within the country has exposed me to the richness of Indian design, colours, and our heritage.

At the same time, the opportunity to witness the confluence of the best while living in London and Rome helped me understand the latest trends in the fashion industry. It is the mixture of the Indian with the global and the past with the present that has been a dominant part of my fashion journey. At some point I have started to think of sustainability as well. Given the extremely rich history of textiles in our country, it was almost natural for me to adapt to them and upcycle to create one of a kind products. I want to showcase the varied and diverse levels of craftsmanship and skills that India has and present it to a global audience.

Your creations are as much rooted in Indian craftsmanship as they are funky and modern. What do you think fashion design means for the 21st century Indian millennial?

The country is on a strong growth and development path. In a manner of speaking, it is almost as if as a nation, we are coming of age and starting to take our place on the global stage. For fashion, this means a certain boldness in expression, a strong sense of identification with Indian-ness. As a generation that has been exposed to so many western influences in lifestyle and clothing, we have created our own versions of design. We are rooted, exposed, aware, and proud. And, having easier access to express ourselves is what has helped an entire generation of designers to truly define and represent a well-rounded idea of the phrase ‘East meets West’. I feel it is important to view oneself as a global citizen when it comes to creating and designing products, but also, at the same time, it is about being aware and proud of where you come from and how you express who you are in a global language and market.

In a world that is moving towards gender-fluid ideas, what has been your experience of situating your shoes in a unique, un-gendered space?

I have always believed in a gender neutral approach to fashion and design. Products aren’t made for genders, they are made for people. Categorising and placing items based on genders is an outdated concept and it is restrictive when it comes to exploring design and style. We cater to all genders and our customers appreciate and understand that approach.

Is there a travel experience that you’d like to take part in that piques your interest?

Having worked so closely with vibrant colors and prints from India and having an extreme fondness for the artisanal approach to fashion, I feel Africa is a continent that I would like to travel to and explore next. Several African countries, much like India, find themselves on the global fashion stage as major markets now. This trend is certainly worth exploring, understanding and taking inspiration from to adapt to one's own work.

Going forward, what are some goals for your brand? What can we expect from Jeetinder Sandhu?

Jeetinder Sandhu has been on a quest to be the brand for all things accessories. Be it shoes, jewellery, home objects, or other small leather goods, I want to tap into various other product categories and be considered as a premium label for all things small, unique, eccentric and bespoke.

Natural Instinct

What would the world look like a few decades from now? While science fiction never fails to add to our already rich imaginations (think: The Creator), things might take a different turn when it comes to urban design, where the focus will primarily be on sustainability. This means more green zones, prioritising eco-conscious building material and an emphasis on recycling. But what would that result in? And would bigger cities become obsolete, as per popular predictions?

Cities will continue to exist, but might look vastly different

Cities are already home to 56% of the world’s population, which is expected to double by 2050. And this need will result in reimagining them. “The truth of it is that cities are living organisms, they alter and change… and they’re unbelievably resilient.” Mary Rowe, president and CEO of the Canadian Urban Institute, told Vox. Across North America, giant office buildings will cease to exist and might be used for housing (given the rising crisis). Downtowns will diversify. Public health and green spaces will take priority.

More focus on community building and nature

RIOS recently presented the Hyper-Abundant City plan at the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism. It reimagines the future of Apgujeong, a neighbourhood in Seoul, to find a solution to urban flooding. They proposed the cultivation of ecological plots to allow for gradual evolution over time. Mexico’s Smart Forest City is another great example. The metropolis would reportedly contain 7.5 mln plants and will be based on the area’s Mayan heritage and its relationship with the natural world.

Newer and smarter cities

Urban population might double, but not necessarily in existing cities and towns. Newer cities, with effective environmental initiatives, are likely to sprawl. And they might look very different from what we imagine a city to be. For instance, Saudi Arabia’s ‘The Line’ is set to become a 100 mile long linear city sans cars and with high-speed autonomous transit.

And this means…

The definition of an ‘urban area’ might change. It might no longer be about concrete jungles, speeding cars, or even a higher population. Instead, it’ll shift to living in sync with nature while equipping societies with modern technology in the most sustainable way possible.

More Than Influential

Thank You For Coming, which recently premiered at the Toronto Film Festival (TIFF), releases in theatres today. While it’s too soon to say whether the film, directed by Karan Boolani, will be successful in throwing light on female sexuality with the kind of nuance the subject deserves, we could not help but notice the interesting cast.

From Kusha Kapila and Dolly Singh to Shibani Bedi, it has its fair share of ‘influencers’. Which brings us to the question: has social media established itself as an alternative platform for aspiring actors? More importantly, has there been a shift in the way people are being cast in Bollywood?

The number game seems to be gaining the upper hand

Influencers have become a critical part of the marketing strategy in most industries, and Bollywood is following suit. People with celebrity status on social media are being cast on the big screen based on the potential benefits they can bring to a project. At the same time, seasoned actors are being questioned on their following – an issue actors Vidya Balan and Huma Qureshi had raked up last year.

Where does this leave the question of fame?

Influencers making their way into Bollywood is one thing, but actors being rejected for not having enough followers is another. Until now, it was an actor’s on screen presence and performance that got them followers and not the other way around. With influencers gaining celebrity status, that seems to be changing. Though, even today, the chances of people recognising and cheering for say, Ranbir Kapoor (who is not on social media) walking down the street, is way higher than expecting a similar reaction for Bhuvan Bam (who has 17 mln followers on Instagram).

So are we to witness more influencers stepping into an actor’s shoes?

Though influencers are regularly being cast in films and shows off late – from Anubhav Singh Bassi in Tu Jhooti Main Makkaar to Kusha Kapila in Masaba Masaba, their roles (for the most part) remain limited and similar to their online personas. So, even as Bollywood’s way of casting people may be shifting, the larger question remains – has the perception of talent changed in the industry or is this yet another phase?

Quiet is the New Loud

Remember when designer labels proudly displayed their names and logos on their products – from clothing to accessories – and so many wore them with even more pride? (who else wishes they had listened to that one friend trying to explain how tacky this looked even back then?)

Well, a reverse trend has been gaining popularity this season, especially with the recently concluded Paris Fashion Week. Conspicuous consumption is passé, with quiet becoming the new loud in fashion – and ‘quiet luxury’ the ongoing trend.

What went on at the Paris Fashion Week?

Besides proving to be a global stage for Indian fashion designers, with the launch of Rahul Mishra’s new label AFEW (and Aishwarya Rai’s moment with Kendall Jenner), minimalism got its revenge on maximalism. Dopamine dressing was replaced by subtlety with an increased emphasis on ‘wearable’ clothes and minimal makeup (Pamela Anderson definitely set an example). Overall, a restrained approach to fashion seems to be settling in, although some designers would disagree.

Pragmatism dominated New York as well

The New York street style collection was more about dealing with the heat wave and clothes to make it through the day cool and collected. From big, boxy button-downs that let in a little breeze to the understated Mary Janes, it was all about comfort. Neutral tones like chocolate, camel, and espresso dominated the ramp. Pleated skirts also made a comeback.

Economic climate is a factor

For long, fashion weeks have marked two ends of the spectrum – one that is for a more niche audience (and exorbitantly expensive) and the other has been street style (not always pragmatic). With more focus on timelessness, affordability, and comfort without compromising on quality, the gap seems to be closing. And a lot of it has to do with the current economic climate.

So, what can we expect?

High fashion becoming more accessible. A Y2K-influenced mood in style translating into subtlety and timelessness and an increased focus on making clothing ergonomic. Essentially, fashion is set to broaden its niche audience.

India Dreamin’: US Ambassador Eric Garcetti on India’s Unlimited Potential

When the US Ambassador to India, Eric Garcetti, visited the country for the first time as a teenager in the 1980s, he immediately fell in love with it. India’s “warmth, cultural heritage, and amazing people” brought him back for a visit again in the 1990s, and many times thereafter.

Though the “trappings and technology” may have changed since his earlier visits, “I’ve also been impressed with how much has remained the same,” he notes. “That incredible richness and vitality is the same as it’s always been.”

It is perhaps these qualities that have evoked a certain zeal in him for India’s generation on the rise. “I think India’s potential is limited only by its aspiration… One of my key goals as US Ambassador to India is to create opportunities for this generation to achieve this potential,” he told us in an exclusive interview.

Catch our conversation with the Ambassador below, where we discuss everything from how he plans to achieve this goal to the Indian cities he is most excited to explore.

India is a nation with one of the largest millennial as well as diasporic populations in the world. What kind of influence are we likely to see this cohort have on the global stage?

I think India’s potential is limited only by its aspiration. Today’s rising generation is stepping into a world of unlimited possibility, as India works with the United States and with partners all around the world to confront the 21st century’s most urgent challenges. The stakes are high, so we need to get this right, but the potential to achieve world-transforming advances has never been stronger.

One of my key goals as US Ambassador to India is to create opportunities for this generation to achieve this potential. We’re working with partners in India and the United States to expand opportunities for a world-class US education; to strengthen supply chains on cutting-edge technology; and to increase deployment of clean, green energy, to protect the planet for future generations.

How is this different from what you encountered during your initial visits to India in the 1980s?

The India of today is different in many ways from that of the 1980’s – after all, not many people back then might have imagined the country landing a spacecraft on the dark side of the moon – but I’ve also been impressed with how much has remained the same.

I first came here when I was 14 years old, and fell in love with the country’s warmth, cultural heritage, and amazing people. I returned in 1990, and many times thereafter, and each time fell in love all over again. The trappings and technology may have changed, but that incredible richness and vitality is the same as it’s always been. Today, I am still filled with wonder as our two countries together write the next chapter of our shared journey.

Last month, you had announced that the US would issue a record number of visas in 2023, while also stating that the US sees India as the “most important country in the world”. As India’s largest newsletter on travel and worklife, we are keen to know the travel and career opportunities our readers can expect in the near future?

The ties between our people are stronger than ever. As we wrap up another record-breaking year for student, employment-based, and immigrant visas, I’ve been blown away by the stories people have shared about their US experiences. Our Embassy and Consulates are working diligently to open the door to even greater opportunities next year!

In your opinion, what is the most underrated Indian food/breakfast item?

Spicy food – anything with chilies. And anything you can eat with your hands. I’m half Mexican, so we eat with tortillas. That’s the way you experience food – with your fingers.

As The Jurni believes you are what you read, which book(s) would we find on your nightstand right now?

Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology by Chris Miller and The Golden Gate by Vikram Seth.

In the spirit of our ethos – “stay curious; never stop seeking” – which Indian city are you most keen to explore next?

Two – can’t wait to get to Pushkar, Rajasthan and Kisama, Nagaland.

Who is your favourite actor/singer/artist from India or the Indian diaspora?

Sharmila Tagore, Shah Rukh Khan, Mindy Kaling, Norah Jones, A.R. Rahman, and Zakir Hussain

An unexpected similarity you’ve observed between Americans and Indians?

We dream the same dreams. We strive for the same ambitions. And we get that same breathless look on our faces when our sports team pulls it out to clinch the match at the last minute.

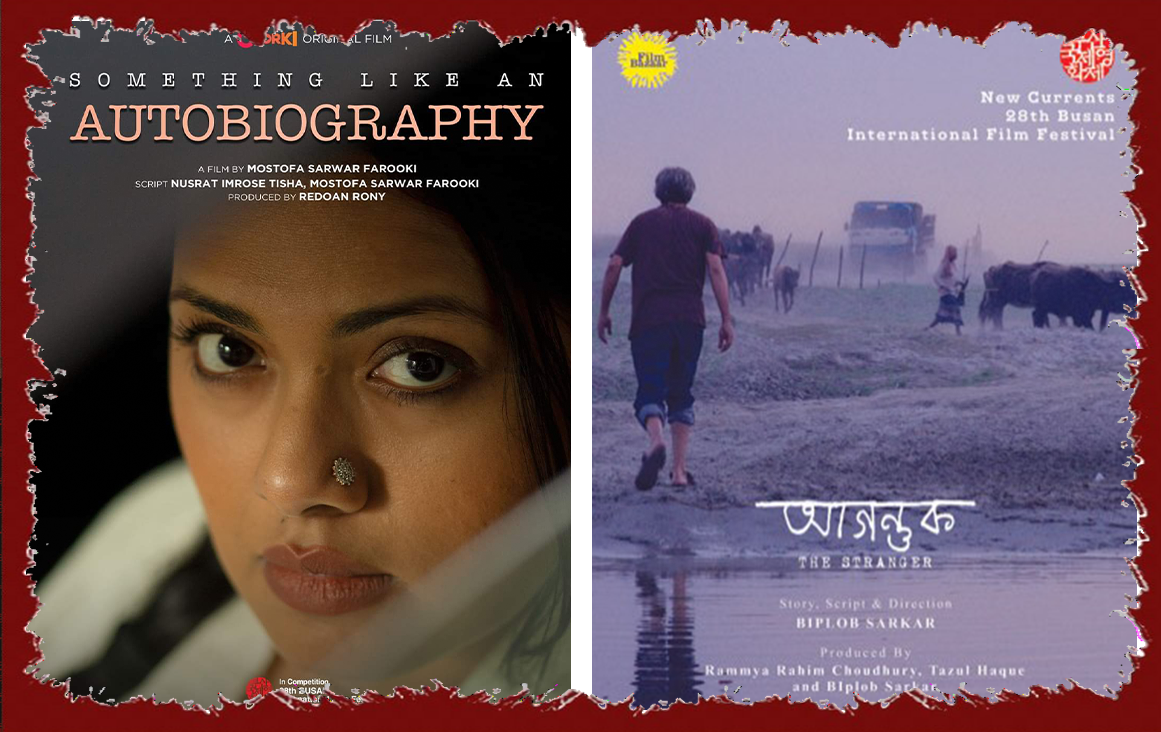

Cinema’s Emerging BFFs

If we ask you to think about a film, say a rom-com based in Korea, would you be immediately able to picture it? Now, let’s change the location to Bangladesh. Would the image be as clear? One of Asia’s biggest film festivals – the Busan Film Festival or BFF – concludes today after screening some of the most thought-provoking films of the year. From Korean Director Park In Je’s fantasy drama Moving, which walked away with several awards, to Hansal Mehta’s crime drama Scoop, which reigned supreme from the Best Asian TV Series category, the range was as diverse as it was captivating.

But more interestingly, it helped us notice the less visible players in the global cinematic landscape – like Bangladeshi and Nepali cinema. So, this National Cinema Day, we thought we’d shine the spotlight on our talented neighbours and celebrate their contribution to world cinema while exploring what’s changed.

Universal themes rooted in local narratives

Be it Bangladesh's Something Like An Autobiography which confronts themes of pregnancy alongside societal and political pressures on celebrities, or Where The Rivers Run South from Nepal, which tackles the issues of migrant labourers and the patriarchy — themes that successfully transcend national borders and are very relatable. At the same time, the films are also deeply rooted in their local milieu, giving us ample occasion to explore and understand the geographical, political, and cultural context of a story.

Bolder storylines

These films are not just tackling certain issues head on, but are experimenting with bold and eccentric themes. For instance, another Bangladeshi film, Agantuk or The Stranger, which was also screened at BFF, explores matters of familial relationships and burgeoning sexuality. On the other hand, Nepal's A Road To A Village is the story of how a family from a remote village grapples with its new reality after gaining access to city life.

So can we expect more in the near future?

Definitely. Just like this year’s BFF proved that all ‘superheroes don’t need to come from North America’, it also demonstrated that good cinema can come from any part of the world. But it will need our support and encouragement. After all, a show without an audience is not much of a show.

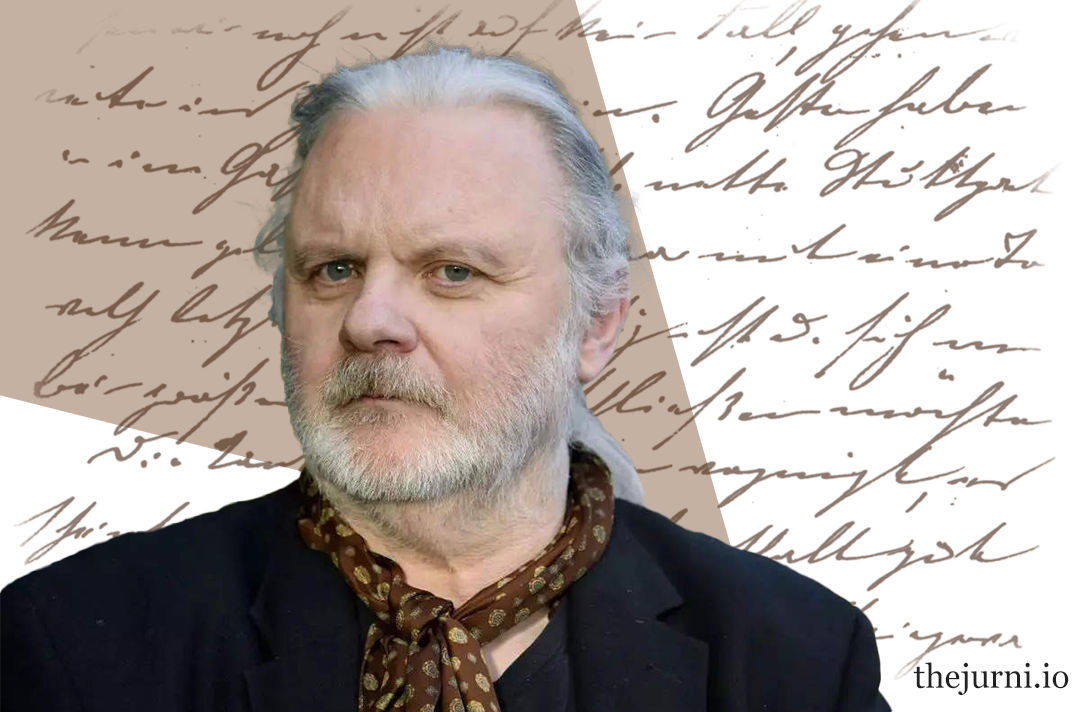

Nynorsk’s Nobel Knight

A curious aspect to this year’s Literature Nobel laureate, Jon Fosse, is that the Norwegian author writes in Nynorsk, a rural language used by just 10% of the Norwegian population, though understandable to most of Fosse’s countrymen. But perhaps this is the very reason why Fosse has been awarded this year.

An author awarded for his “innovative plays and prose which give voice to the unsayable”, Fosse is known as a writer with a sparse and minimalist style that seeks to push the boundaries of what can be achieved with experimentation. Dream of Autumn (1999), which shot Fosse to fame outside Norway, is an exercise in bending space and time in theatre.

In case you feel that is too avant-garde, Fosse’s magnum opus, Septology, is a three-volume tome that consists of a single sentence. The narrative follows two painters who share the same name and are neighbours, but do not interact. The book’s third volume was nominated for the 2022 International Booker.

The bleak and existential nature of his subjects, as well as his voice, has led to Fosse being anointed ‘the 21st century Beckett’ by Le Monde (His 1996 play, Someone Is Going To Come, is based on Waiting For Godot). With an astonishing oeuvre consisting of 40 plays, over 70 novels, and a multitude of short stories, this introspective writer is likely to overtake his former student, Karl Ove Knausgård, as the best known Norwegian writer.